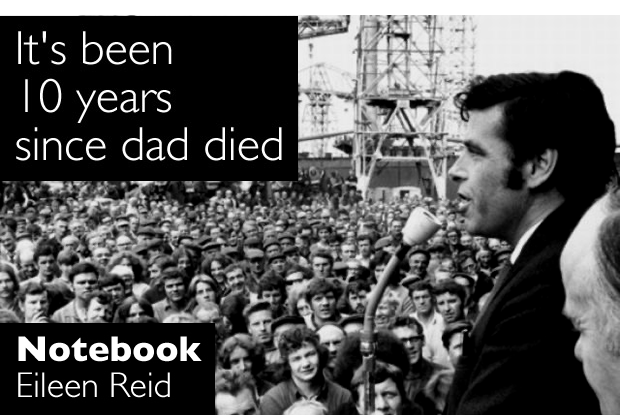

On Monday 10 August, it was precisely 10 years since dad died. Ten years. Grief doesn’t magically end following a period of mourning. Reminders such as birthdays, anniversaries, and memories triggered by prosaic events compound the loss of him, over and over. Then there are new events â such as family weddings, birth of his great-granddaughter â and personal achievements that we know would delight him. Similarly, though, serious illnesses and other unhappy events have us thinking, thank goodness dad isn’t here, he would’ve been devastated.

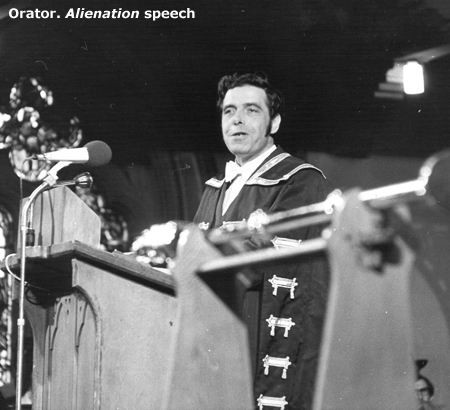

Over the last decade, there have been many such triggering occasions. As a public figure and orator, video clips of part of his speeches stop me short. That magnificent head with his dark wavy hair (which he never lost) pops up on screens unexpectedly. The most unnerving trigger is his voice. Shortly after he died in 2010, as a family we were invited to an Aye Write event where the actor, David Hayman, was to recite dad’s famous rectorial address, Alienation. As we entered the packed auditorium, that familiar, booming, beautiful voice reverberated over the speaker system. As a family, we trembled with the sheer force of it: he was gone, but somehow very much alive.

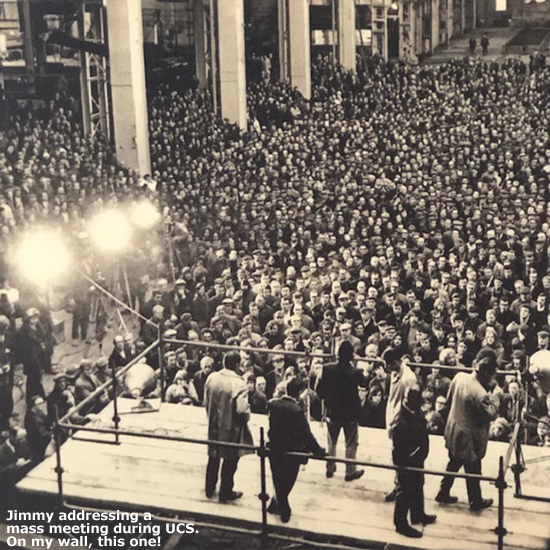

Strangely, that latter thought â pervasive in my mind despite having little if any religious hankerings â through good times and bad, has been with me for a decade. This strangeness has not been unpleasant. Lying in hospital critically ill, I kept close a photograph of him outside the shipyard (see below), where I believed he and his fellow shipyard workers were willing me on to get better.

I remember calling one of dad’s closest friends, David Scott, to tell him dad had died. Although the news was not unexpected, it was a shock. After ringing off, I called David back minutes later, anxious that dad may have been forgotten, and that we should place a death notice in The Herald. People who knew Jimmy could be informed, I said, and hopefully attend his funeral during the holiday period. David paused awhile before responding, ‘Darling,’ he said, ‘I don’t think you need to put a notice in The Herald‘.

Blimey, the next morning I realised why David had paused. Press coverage of dad’s life and his passing was reported nationwide in every newspaper and media outlet. Hundreds of moving letters from people from all walks of life were gratefully received by our family. It was an extraordinary period of grief, but also of enormous pride.

Our dearest possession is life

I was overwhelmed with relief by the wonderful tributes to dad. In the weeks leading up to his death, in a moment of lucidity when he seemed to know he was going to die, he asked me whether I thought his life had been worthwhile. Perhaps he had been thinking of Nikolai Ostrovsky’s famous creed (which dad had framed on his wall): ‘Man’s dearest possession is life. It is given to him but once, and he must live it so as to feel no torturing regrets for years without purpose⦠so live that dying he can say: All my life and all my strength were given to the finest cause in the world â the liberation of mankind’. A Communist Party creed, yet I don’t think it ever left him, even if he left the party. Although a stringent, all-consuming imperative for any man or woman to live up to, I reassured dad that his life’s efforts had not been in vain.

Fairfields

By the day of his funeral, we had an inkling of what to expect. Still, as the funeral cortege pulled into the Govan Road on its way to Govan Parish Church, the sight of hundreds of shipyard workers lining the streets outside ‘Fairfields’ was profoundly moving. I found myself smiling that day. I kept talking to dad: ‘See? Look at this dad. Of course, your life was worthwhile’. If ever there was an event that I wished he’d witnessed, it was his own funeral. Billy Connolly’s eulogy was hilarious, Alex Ferguson’s captured the spirit of working-class Govan, Alex Salmond’s was an eloquent, non-partisan tribute. Kenneth Roy conducted a thoughtful more private, family service in Craigton crematorium. I spoke at that. And through it all, dad was there.

Jimmy, the orator

As to his legacy, Jimmy was a superb orator, and spoke fine, motivating words with immaculate timing and emphases. His most famous speech, Alienation, delivered to students in 1971, is held by many â including the recent rector of Glasgow University, Aamer Anwar â to be ‘as relevant today as the day Jimmy gave his speech’. ‘His words,’ said Aamer, are ‘a constant reminder of what is possible for humanity to achieve’, and still cited to this day.

Particularly relevant currently is Jimmy’s challenging message to Scottish education: ‘If automation and technology is accompanied as it must be with full employment, then the leisure time available to humanity will be enormously increased. If that is so, then our concept of education must change. The object must be to educate people for life, not solely for work or a profession’.

And of course, there was the UCS work-in speeches, particularly his renowned plea to the shipyard workers. In the ambulance on the way to Inverclyde hospital in 2010, where he died four weeks later, the young ambulance men, who recognised him yelled: ‘Hey Jimmy, you’re the most famous shop steward in the world! Nae bevying!’

His rallying call to the shipyard workers, with immaculate timing and pauses, advocating a radical work-in, is worth quoting in full: ‘We are not going to strike. We are not even having a sit-inâ¦There will be no hooliganism. There will be no vandalism. And there will be no bevying⦠because the world is watching us and it is our responsibility to conduct ourselves with dignity, and with maturity’. Sure enough, the UCS work-in was one of the most strategic, well-organised, dignified, disciplined and effective struggles in working-class history. It drew worldwide support from across all classes, parties and professions. A type of political ecumenism rarely seen, before or since.

James

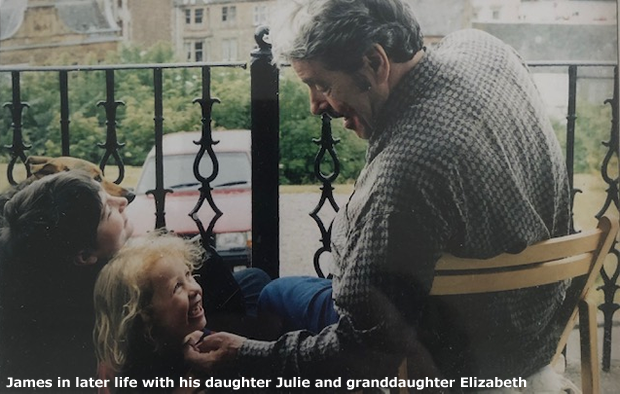

Jimmy the public figure was also James, a family man. He was good-natured, kind, loving and was much loved in return. He was also very noisy, perhaps because his hearing wasn’t, eh, terribly acute. He told wonderful stories, talked politics, sang a lot, and even danced. He made us laugh frequently, and loudly. He absolutely adored his granddaughters, and they him. Our family home was rambunctious.

Shortly after he died, as I was sitting in his comfortable study on his battered leather chair, I became aware of a strange ticking. Where is that sound coming from? On the mantlepiece for years, was his old clock. I had never heard it tick before. In fact, I didn’t even know it had a tick. A huge, silent, empty sadness descended at that moment, which in truth has never left me, or our family.