It was in the back room of the Hare and Hounds in Islington that I first met Ian Jack (1945-2022). That neglected space in Upper Street had been given a new lease of life in the late 1970s by the much missed musician Robin McKidd. Robin, originally from Dundee, played with a band called Alive’n Pickin and he had persuaded the despairing landlord to give the band a regular Sunday night residency in that dingy chamber. As the boys would play for next to nothing, the landlord didn’t have much to lose.

It was probably one of the best decisions he ever made. The takings on those joyous evenings rocketed as the honky tonk atmosphere of rockabilly, country and traditional music attracted a lively and thirsty following. Including a fair smattering of the diaspora of Scottish journalists and media folk who treated Highbury and Islington like Australians treated Earls Court.

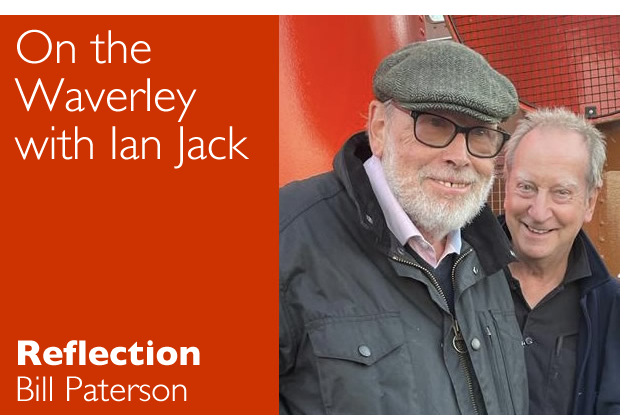

Some of these scribblers had achieved considerable fame and among them was Ian Jack. Ian was one of the less raucous regulars and we struck up a friendship which lasted until our final outing last month on his beloved PS Waverley.

Over the years we would meet for walks, talks and ‘pensioner’s lunches’. All the time gossiping and mulling over the fractured state of the nation we lived in and, very often, the state of the Scotland we had left in the 1970s.

Spiced, in later years, by Ian’s updates from his cherished new home on Bute.

I learned early on that his great talent was for listening and filing away material for future reference. The ideal, if risky, companion for a chatterbox actor.

Our backgrounds had much in common but were enlivened by a few crucial differences which made the conversations all the more stimulating. At least for me. We had been born four months apart in 1945. Ian, a February baby, always claimed to have a more intimate knowledge of the Second World War because he had arrived in plenty of time for VE Day. I had missed it by three weeks.

The Scottish segment of Ian’s upbringing had been in Fife whilst all of mine had been in Glasgow and on the Clyde coast. My father travelled the west coast for the plumbing trade and I had aunties in Dunoon and a holiday every single year in a wee room and kitchen in Millport on the Isle of Cumbrae. This meant that by the time I was a teenager, I had sailed on most of the steamers belonging to the Caledonian Steam Packet’s Clyde Coast fleet. I was ticking off my bucket list while the golden age of Clyde cruising steamed quietly towards the breakers yard.

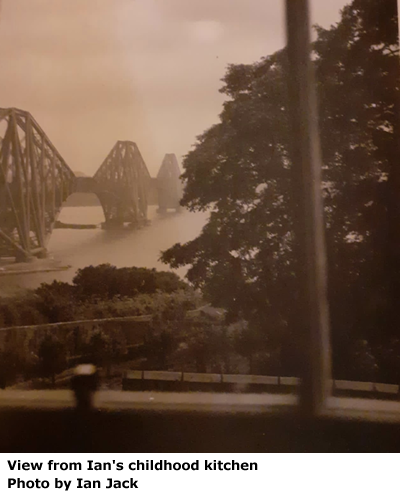

This gave Ian cause for mild envy but he had been well compensated by the vista of the Forth from his childhood kitchen in Inverkeithing. That view probably explains everything.

On that final October cruise on the Thames, someone asked where the Waverley had been built. I suggested ‘Denny of Dumbarton’ but Ian gently put me to rights. ‘A and J Inglis, Pointhouse. 1947, 694 tons.’ He could have told us where the onboard scones had been baked but nobody asked. This comprehensive fascination with industrial and social history was the bedrock of his long form articles.

He could link the building of the paddle steamer Jeanie Deans at Fairfields in 1931 with the local heroes involved in the UCS work-in 40 years later, through to the yard becoming the last presence of real shipbuilding on the Clyde as the multi-billion pound defence behemoth BAE. Most importantly, he made these links unforced and natural.

His forensic 2016 examination of the history of the Trident nuclear presence at Faslane was made personal by his love of the landscape he could see from his sitting room in Rothesay. It was a brilliant piece but, ever the perfectionist, he asked me to record it for a Guardian podcast simply because he said that if he had to read it aloud he would want to rewrite every word.

Coming up to date, if you’re looking for the lowdown on the current ferry fiasco at Port Glasgow, don’t wait for the inevitable multi-million pound inquiry. Just read the 18,000 words of his blistering piece for the London Review of Books. That piece will fill you in for the price of a coffee.

As befits a wee boy who grew up looking at the Forth Bridge while having his cornflakes, he would write about the giant locomotives trundling down from Cowlairs, hoisted on the Finnieston crane and thence across the oceans to serve the great railways of India. Calcutta, later Kolkata, was his second city and his dispatches from Bengal were as insightful and original as anything he produced.

This wisdom was always lightly worn. Ian didn’t go in for virtue signalling and he didn’t write for an echo chamber of opinion. His hallmark was a sort of progressive nostalgia that threw the light of the past on to the present.

Naturally, over our coffees, we talked an awful lot about Scotland and any possible breakaway from the union we grew up with as boys. This invariably brought us back to the state of the Clyde Coast piers which Ian used so much. They became a metaphor for how things could be in a Scotland which made its own decisions.

Why were they now so ugly and forbidding with so little care for their Edwardian elegance and scenic settings? Were those industrial scale vehicle loading ramps planned in Edinburgh or had we been told to build them by a wicked Englishman? We could never decide.

While on our musings, I would often get quite agitated by the glacial pace of the Scottish items passing through the online coverage of The Guardian. They could hang around for days and give the impression that nothing more important was happening north of the border. Sometimes though, that is as it should be.

A very fine obituary and many warm appreciations sat on the site for even longer than usual and gave Ian a week of top billing. Even above Jerry Lee Lewis who had passed away on the same day.

After years of superb contributions to the paper, he certainly deserved that. On that crystal clear October evening, the PS Waverley steamed through the raised bascules of Tower Bridge and we finally moored in the heart of glittering moneyed London. As I dropped Ian off at Highbury, it seemed that another engaging piece could be taking shape under that tweed bunnet. I hope he found time to write it.

Bill Paterson is an actor and commentator